This year, CultOfWhatever is looking back on some of the most influential, transformative, genre-defining, and cult-favorite films of 1999. We began in January with a look at M. Night Shyamalan’s breakout hit: The Sixth Sense. It’s a horror-thriller that stands the test of time and works as a great movie that would have been great in any year of release. M. Night could have made this movie yesterday and he would have had a smash on his hands. He could have released it in 1989 and it would have been just as tremendous.

We then looked at Fight Club, a movie very different from The Sixth Sense. It was very much a product of its time and time has not been good to it. It’s obnoxious, pretentious, gritty but undramatic, and the twist at the end was flat compared to Shyamalan’s first big shocker.

In March we reminisced about the bygone fun of The Mummy, a film that has certainly held up, precisely because it leaned heavily on the past and on its Indiana Jones inspirations. Already we have a tremendously eclectic few movies. One modern-day thriller/horror, one gritty 90’s-esque macho-fantasy, and one 1920’s-set throwback.

The variety continues this month with 1999’s Star Wars killer, The Matrix.

The previous sentence needs an explanation.

At first glance, it seems wholly inaccurate. The Matrix didn’t kill Star Wars. Far from it; later this year Episode IX will release to expectedly humongous box office numbers while The Matrix movies fizzled out with The Matrix Revolutions in 2003. Since then there’s been…nothing. No further sequels, no side stories, no literary expanded universe. The films exist within a tight, five-year bubble and no more. Star Wars is an institution; The Matrix is not.

And yet, in 1999 The Matrix was to Star Wars what Nirvana’s Nevermind was to Michael Jackson’s Dangerous. The latter sold more copies in 1991-1992 but the former landed a shot across the bow that signaled a shift in taste. Michael Jackson’s follow-up to BAD was unseated from the top of the charts after only two months and the King of Pop never really regained his crown.

Likewise, Star Wars owned the media in 1999. With the beginning of the Prequel Trilogy, everyone entered the year expecting George Lucas’ franchise to dominate the collective consciousness for the next decade. Instead, when the year ended all any genre fans could talk about was the movie that came in fifth place at the Box Office for the year.

It’s hard to underscore just how much of a cultural shift 1999 was to modern movies, but when people talk about the films that drove the new wave of cinema, they don’t talk about Episode I; they talk about The Matrix.

Whereas The Phantom Menace played it safe, The Matrix took risks.

Star Wars returned to cinemas with a story lacking in hard edges. The old favorites were there, Tattooine, lightsaber fights, space battles, but it all felt hollow. It felt overly manufactured. The rebellious energy of the Original Trilogy—made by a director/producer with something to prove—was replaced by a factory-made product, made by an entertainment mogul looking to sell toys.

In the Prequels, the environments all had a glossy, plastic-looking quality to them. The intention was to show how the galaxy was before the Empire corrupted everything. The result, however, was a universe that looked and felt fake, in large part because so much of it relied on late-90’s computer-generated visuals.

The Matrix, on the other hand, was dirty, lived-in, duct-taped together, just as the first Star Wars movies had been. Whereas Episode I was bright and colorful, like a cartoon come to life, The Matrix played around in stark tones of Black and Green. When in the Matrix, everything was washed in a pale green hue, subconsciously evoking the artificial nature of the world. The characters, however, dressed in black. Black leather, black trenchcoats, black suits; there was a slick coolness to it. Lots and lots of kids dressed up as Darth Maul for Halloween that year, but a great number (many more than anyone could have imagined before release) dressed up as Neo or Agent Smith.

In terms of philosophy, the Original Star Wars movies never went too deep but they did turn “The Force” into something just mystical enough, and just explained enough to captivate an entire generation. For the follow-up films, Star Wars instead settled for a flat “chosen one” prophesy narrative, eschewing the mysticism and mystery of the original movies, and replacing the “energy that surrounds us and binds us” with “microscopic organisms that live inside your body.”

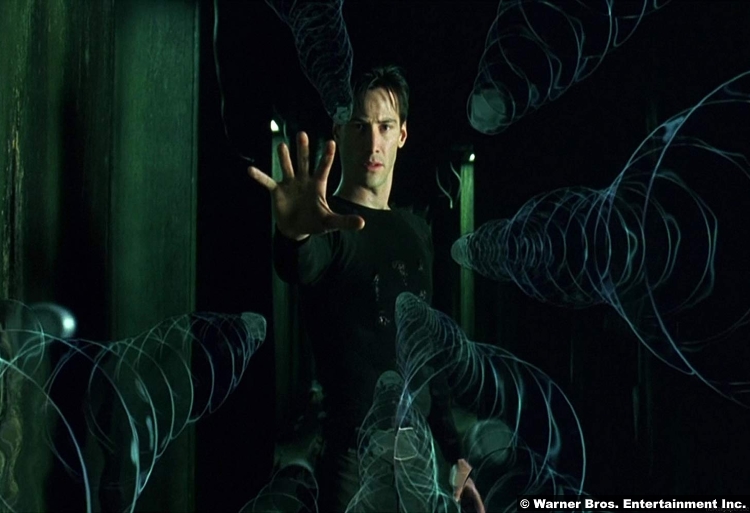

The Matrix, on the other hand, doubled down on its philosophical trappings. It too had a chosen one narrative, but it injected doubt into whether or not that narrative was a myth. Even today there are questions about Neo and The Matrix, whether the “real world” he escaped to wasn’t just another level of reality created by the machines. The depth continues to be debated whenever the movie is brought up, whereas the subtext and philosophy of Episode I is mostly ignored (and easily ignorable).

Episode I is remembered as a pioneer for visual effects, in the way it brought a fully-realized CG character to life. When you put it that way, it’s a great achievement. When you remember that the character in question was a walking ethnic stereotype who made literal poop jokes, the impact lessens a bit. JarJar Binks was brought to life by the most famous VFX designers in the business: Industrial Light and Magic. Their creation was very much a style over substance product, however. JarJar was a brilliant piece of technology but the usage of that technology was a wasted on an off-putting character.

In contrast, The Matrix‘ effects were handled by a mostly unknown studio: Manex Visual Effects. They had none of the pedigree of ILM and far fewer resources, yet they created something that instantly became a pop culture phenomenon. While everyone was spending the summer of 1999 mocking JarJar Binks, people were also trying (and failing falling) to recreate the “Bullet Time” sequence seen in The Matrix. When it was time to hand out Oscars, it was the underdog Matrix that walked away with the “Best Visual Effects” award, beating out The Phantom Menace and its revolutionary (but wasted) creation.

We’re a thousand words into the article and have said very little about the actual movie of The Matrix. And yet, that’s not really the story here. The Matrix is known though not often considered anymore, at least not directly. It never became the big franchise that Star Wars was and remains. Instead, its story is as the vanguard of a new wave of cinema. Like Nirvana kicked the pop off the top of music and ushered in the era of Alternative Rock, so too did The Matrix unseat the kind of movie that Episode I represented: big, bombastic, self-referential. Look at the sci-fi movies that followed 1999, how many tried to copy what Star Wars (the top grossing movie of the year) was doing? How many tried to copy the black leather, sunglasses, bullet time, hard edge style of The Matrix?

That’s its legacy.

And though it failed to create a memorable franchise for itself in 2003, it doesn’t matter. The film remains important for its legacy. And though its sequels struggled to repeat the spark that the first film lit, the first film remains a classic. Episode I may be part of a huge franchise, but few (objectively) look back on it fondly. The Matrix, on the other hand, remains worthy of fond memory. It is gritty, unconventional, genre-defying, visually stunning, and still awesome…twenty years later.